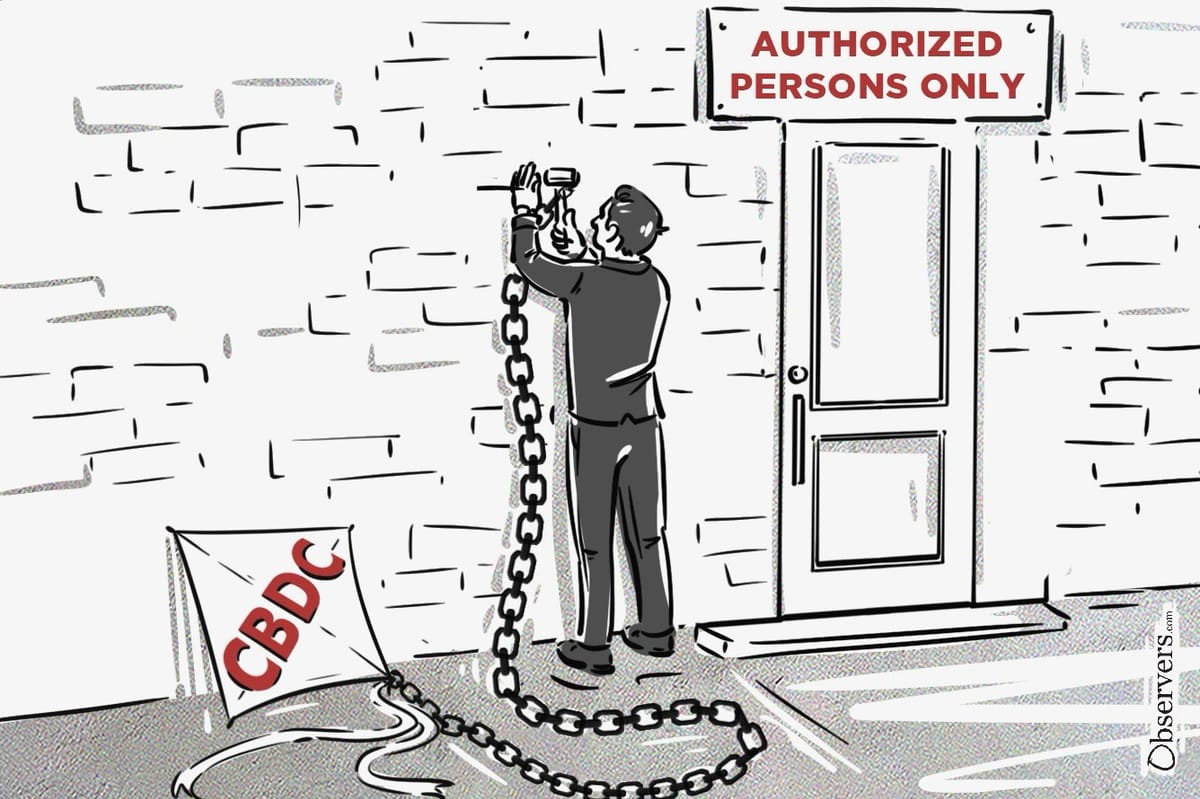

Will Central Banks' Money Fly?

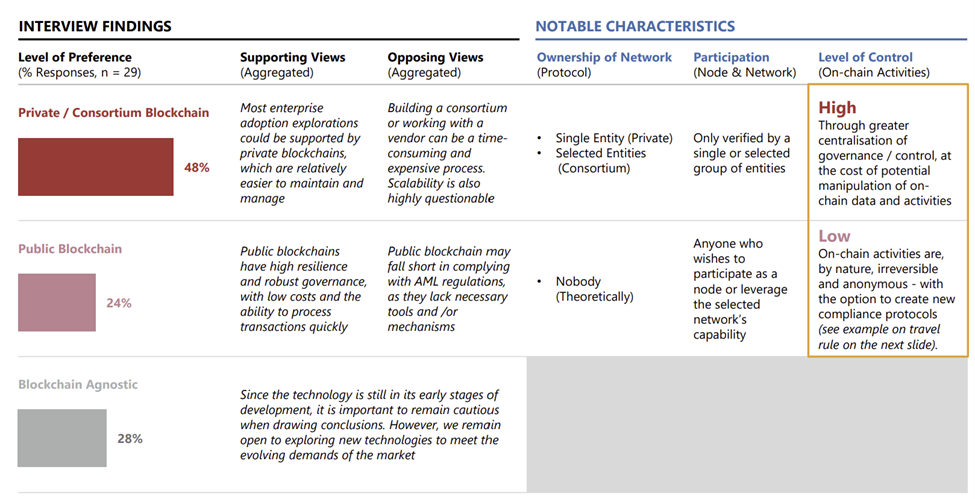

As central banks build digital currencies with tight control, they abandon the core innovation of blockchain—permissionless design. While CBDCs favor private ledgers, the U.S. turns to stablecoins running on public rails, balancing decentralization, oversight, and market-driven innovation.