The crypto community began discussing DAOs during the 2016–2018 ICO boom, fueled by widespread enthusiasm for decentralization. The prevailing logic was simple: if the technology is decentralized, its governance should be too.

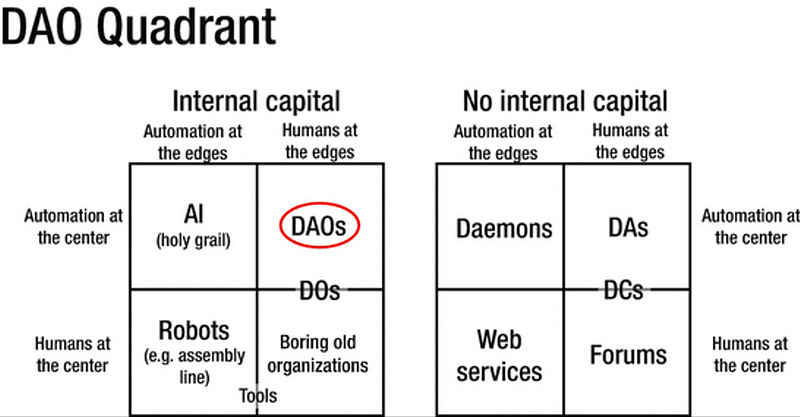

New models emerged that framed DAOs as a breakthrough enabled by blockchain and smart contracts—tools that allowed automated, trustless coordination.

Like other experiments in decentralized systems, DAOs were typically launched as low-stakes, early-stage projects, with the intention to evolve alongside the protocol’s growth.

However, few acknowledged a fundamental challenge: organizing large, distributed communities to consistently propose ideas, vote, and stay engaged is extremely difficult—especially for smaller projects.

In practice, governance often ends up in the hands of a small team of committed, incentivized contributors. This setup tends to be more efficient than relying on thousands of passive token holders.

Moreover, many DAO token holders remain disengaged. While they may hold voting power, few actively participate. A Cambridge study published in December 2024 found that in several leading DeFi protocols, a small number of individuals controlled the majority of governance power.

This concentration opens the door to governance attacks, where a few actors push through decisions that benefit themselves at the expense of the broader community. On the other hand, these actors often claim they are preserving the project's original mission and defending against hostile takeovers by external capital.

Several such conflicts have occurred in DeFi over the past year:

- Compound Whale Governance Attack. A small group of whales coordinated a governance proposal that fundamentally shifted protocol parameters due to voting power concentration, demonstrating how capital-driven control can override broader community intentions.

- MakerDAO Emergency Governance Move. A significant governance drama occurred at Maker (now Sky). In February 2025, an emergency proposal to increase MKR-backed borrowing limits passed after being fast-tracked—reports say some voices were removed from forum discussions. The move sparked allegations of a “governance attack” or attempted power grab disguised as risk management.

- Uniswap Governance Opaqueness. Although no direct “override” event, Uniswap has faced scrutiny for the influence of large token holders and the opaque nature of its off-chain governance. A prominent case involved a16z using 15 million UNI tokens to influence a vote on integrating the Wormhole bridge—a move seen by some as prioritizing capital-weighted interests.

Drop the DAO and Move Faster

As a result, a growing number of projects are scaling back or even shutting down their governance DAOs. Just in the last month, two notable examples—Jupiter DAO and ApeCoin DAO—began winding down their decentralized governance structures.

In the case of Jupiter DAO, tensions had long simmered between the team and the community. Many were frustrated by the team’s outsized influence over voting. One community member voiced the broader sentiment:

“There is no governance. I don’t understand why this vote even existed if the team was going to interfere. Putting something up for the ‘community’ to decide, when in reality the team is deciding for them.”

Ultimately, the team decided to suspend the DAO altogether.

The decision left a lot of people wondering what the point of having a DAO even was, if the team could just step in and override it. What made things worse was that the call was made privately, without any vote, which didn’t sit well with many in the community.

On their side, the Jupiter team said the current DAO setup just wasn’t working anymore. According to them, the next few months would be critical, and moving forward would require everyone — the team, token holders, contributors, and the wider community — to be on the same page.

“The current DAO structure isn’t working as intended. We hear the complaints. We see the breakdown in trust. We feel the perpetual FUD cycle that grows with every vote. Instead of the DAO, holders, and team working together to push the platform forward, we’re stuck in a negative feedback loop.”

Although they didn’t scrap the DAO entirely, the team paused all DAO voting until the end of 2025 and pledged to develop a better governance model.

ApeCoin DAO is another project facing similar issues. Unlike Jupiter, however, ApeCoin’s team chose to sunset the DAO through an actual governance vote, so far receiving 99.66% approval. According to the team:

“While the DAO was instrumental in bootstrapping ApeCoin’s early momentum, it has become misaligned with the future we must build. The next chapter demands sharper focus, faster execution, and a model that backs only the highest-caliber projects.”

The DAO had suffered from similar dysfunctions: lack of focus, slow execution, and low-quality proposals.

“What started with promise has devolved into sluggish, noisy, and often unserious governance theater. Too many resources have gone to vanity proposals and low-impact initiatives.”

Going forward, project management will be handled by ApeCo, a new entity created by Yuga Labs. Its mission is to strengthen the APE ecosystem by supporting top-tier builders and focusing on three core pillars: ApeChain, Bored Ape Yacht Club, and Otherside.

While Jupiter and ApeCoin may be early examples, they likely won’t be the last.

What Do the Founding Fathers Think?

In his 2022 post, Vitalik Buterin acknowledges that DAO governance is far from perfect, especially in scenarios where decentralized decision-making becomes inefficient or confusing.

He distinguishes between two types of decisions:

- Concave decisions – like public goods funding or judicial matters – benefit from diverse, community-driven deliberation.

- Convex decisions – such as emergency protocol changes or military-like strategic moves – often require centralized, decisive action.

When governance falls into the wrong category, decision-making becomes inefficient or ineffective.

In more recent posts, Buterin discusses AI-assisted DAO structures and also possible improvement of the voting mechanisms by shifting from traditional transparent to private voting as in NounsDAO example.

At their core, DAOs face two intertwined challenges: the inherent difficulty of large-scale human coordination and the technical isolation of blockchains from real-world context. Getting a globally distributed group of token holders to propose, debate, and execute decisions efficiently is already a steep task—one made harder by apathy, misaligned incentives, and information overload. On top of that, most DAOs operate entirely on-chain, yet governance often requires interpreting off-chain events, making judgment calls, or adapting to shifting market realities.

Resolving these issues will take time, and for now, we Observe the experiment unfold.