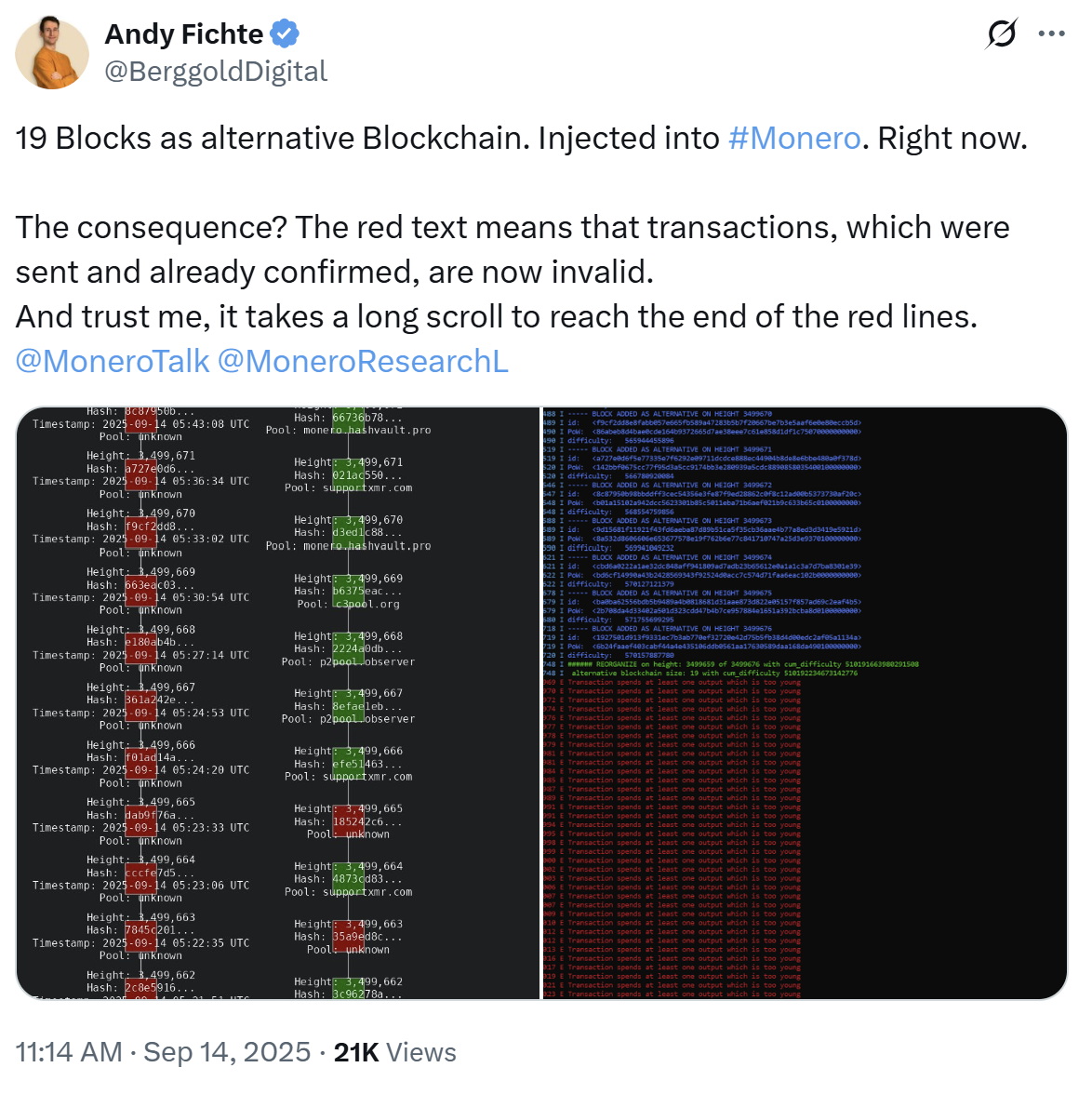

Monero, the leading privacy-focused cryptocurrency, has become the target of an attack carried out not by outsiders but by its own miners. On September 14, the network suffered a rare blockchain reorganization in which about 18 blocks were replaced on the main chain. The event demonstrated that the group behind Monero’s largest mining pool is capable of executing a 51% attack — temporarily seizing majority control of the network’s hash power. Technically, this amounts to a network takeover.

In proof-of-work (PoW) blockchains such as Monero and Bitcoin, transactions are considered “final” once they are buried under multiple blocks in the longest chain. Miners compete to add new blocks by completing computational work. The chain with the most cumulative work is recognized as the valid history. A reorganization (reorg) occurs when a competing branch overtakes the previously longest chain, discarding older blocks and the transactions inside them.

Qubic’s Useful Mining

The project behind Monero’s recent takeover is Qubic, founded by Sergey Ivancheglo, better known in the crypto community by his pseudonym Come-From-Beyond (CFB). Ivancheglo is a prominent figure in blockchain history: he created NXT, one of the first Proof-of-Stake blockchains, and later co-founded IOTA. Qubic was originally envisioned as an IOTA side project but later evolved into an independent platform under Sergey’s leadership.

Qubic's distinctive feature is a “Useful Proof of Work” (uPoW) system. Its miners, called Computors, not only generate hashes but also perform useful computations such as AI model training. This dual-purpose design means Computors earn both from traditional mining (like Monero) and from outsourced AI training tasks, with rewards distributed through the QUBIC token.

In May 2025, Qubic announced that its Computors could direct their computing power toward Monero (XMR) mining, integrating Monero rewards into its incentive loop. According to Qubic's reports, their miners were earning up to 3× more than independent Monero miners. What followed was a rapid consolidation of Monero’s hash power:

Within one month, Qubic miners accounted for 10% of Monero’s hashrate. Two months later, their share doubled to 20% and by late July 2025, Qubic’s controlled 40% of Monero’s mining power.

On August 12, Qubic announced that its miners had briefly seized 51% of Monero’s hashrate, framing it as proof of a network takeover.

The Monero team acknowledged that a six-block reorganization had occurred but rejected Qubic’s claim of sustained majority control. Analysts at BitMEX Research noted that while the reorg was real, it could also result from short-term variance rather than a permanent 51% dominance. Community figures like Luke Parker of Serai and Seth of Cake Wallet echoed this skepticism.

However, as a strong indication of underlying problems, centralized exchanges swiftly raised their security thresholds. Kraken, Binance, and OKX increased the required number of confirmations before XMR transactions would be credited, citing heightened reorg risk.

On September 14, Monero suffered the deepest blockchain reorganization in its history, with 18 blocks replaced (from block 3,499,659 to 3,499,676). The rollback erased roughly 36 minutes of transaction history and invalidated around 117–118 transactions, making it the largest reorg ever recorded on a major blockchain.

Sergey Ivancheglo (CFB), in response, denied that the reorg had caused any transaction loss. Posting on his X page, he claimed that “not even a single Monero transaction was invalidated.”

Why Monero?

Monero is not just another blockchain — it is the leading privacy protocol, with a large, loyal community that treats it as a cornerstone of crypto’s independence. An attack on Monero is therefore read less as market competition and more as an assault on the core principles of decentralization and financial privacy. Unsurprisingly, rumors circulated that Qubic’s founder, Sergey Ivancheglo (CFB), might have been backed by state actors to weaken Monero. There is no public evidence for that claim, but the symbolism of targeting Monero was impossible to ignore.

A more plausible motive is simpler: Monero is one of the largest PoW projects by market cap and community engagement, so it offered Qubic the highest-visibility stage. Monero’s RandomX algorithm is CPU- and GPU-friendly and was designed to resist ASIC centralization and keep mining broadly accessible. The trade-off is that if enough cloud compute or redirected hardware can be mobilized, RandomX networks can become suddenly vulnerable to hashrate concentration — exactly what Qubic exploited.

Are Proof-of-Work Blockchains Vulnerable?

The Monero episode opens a new vector of risk for PoW chains. In its August release, Qubic framed the experiment as a learning exercise and distilled a blunt lesson:

“Incentives dictate consensus — any PoW chain can be captured if superior economic incentives are offered.”

That truth is unnerving because it points to an economic, not purely technological, attack surface.

Bitcoin miners collectively earn on the order of tens of millions of dollars per day from block rewards and fees (a commonly used round figure is ≈ $20M/day). Framed as an economic problem, flipping miners’ loyalties is therefore about matching — and exceeding — what they currently receive.

In simple terms, to convince a majority of miners to point their rigs at a hostile or “predatory” pool you would need to promise them more than that daily revenue in extra payouts or side-payments — a back-of-the-envelope incentive on the order of $40M+/day, and in practice likely materially higher because operators demand a risk premium.

Bribing existing miners therefore looks like the more realistic pathway to majority control. The Monero case shows how attractive economic incentives can re-shape hashpower quickly without buying a single ASIC: subsidize miners (or pay them in another token) and hashpower can consolidate. That dynamic is the most immediate and worrying attack vector for PoW networks — it requires neither exotic technology nor quantum breakthroughs, only deep pockets and effective incentives.